Fernando Sor’s fantasias are among his best works. Even when they are less successful they are still among his most interesting. Like many other nineneeth-century fantasias, they often use a theme-and-variation form wherein there is an extended introduction, followed by variations that eventually break from the structure of the theme, and finally a novel, and often spectacular, coda. Op. 30 goes the furthest in this regard, ending with a sonata form movement. The Fantasia in D Minor does something similar, ending with what is essentially a sonatina.

However, a few of Sor’s fantasias, such as Fantaisie elegiaque, do not use theme-and-variation form. These fantasias are usually attempts at something experimental, and this partly explains their flaws. The two most interesting are the Fantaisie elegiaque and the Fantaisie villageoise. The latter is in my opinion a better work, though it shares some of the same weaknesses as elegiaque — namely that the music takes a while to move forward, in ways that are not always, at least in the first half, sufficiently interesting. These structural problems are more forgivable in villageoise, however, as it is supposed to be a musical collage that conjures an image of village life. Its evocation of peasant dance is truly striking, as is the use of harmonics (and very strange harmonics at that) to depict church bells, which announce and then interrupt a simple piano chorale.

My feelings about the Fantaisie elegiaque are more ambivalent. On the one hand it is a remarkable work within the context of nineneeth-century guitar music: a long, 15-20 minute unrelenting elegy that is so different to nearly everything else in the repertoire (indeed Sor was the only nineteenth-century guitarist-composer who produced such strikingly ‘new’ works).

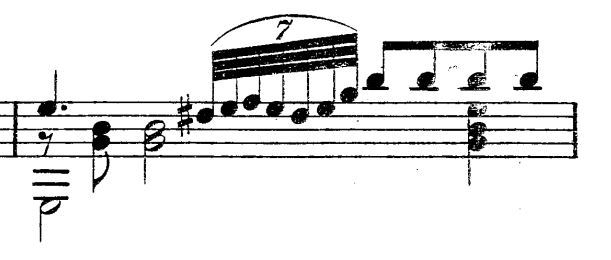

It has many curious qualities, including the opening forte, diminished-seventh chord:

For the next six pages (you can download the score from IMSLP) there are no contrasting movements. The tempo ranges from andante largo in the introduction (which makes up 3/5ths of the work) to andante moderato in the funeral march. None of the music is especially virtuosic — it might be easiest long-form work by Sor, technically speaking.

There are many excellent moments. One particularly fine section is reminiscent of lute/vihuela music (or possibly the Renaissance choral music Sor would have been exposed to as part of his musical educations, which mostly took place at the choir school of the monastery of Montserrat). The way Sor leads us to it is one of the most beautiful moments in the work (12:03 in the video recording several paragraphs below).

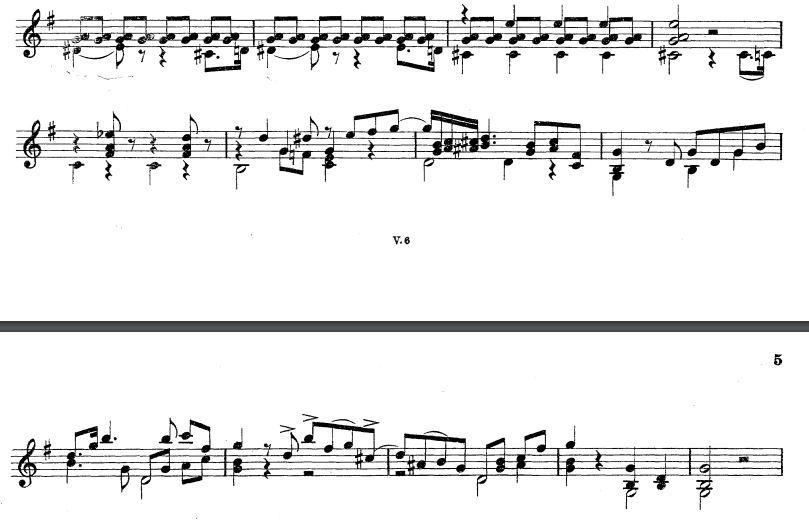

There are moments of Chopin in it, such as Sor’s use of ornamentation:

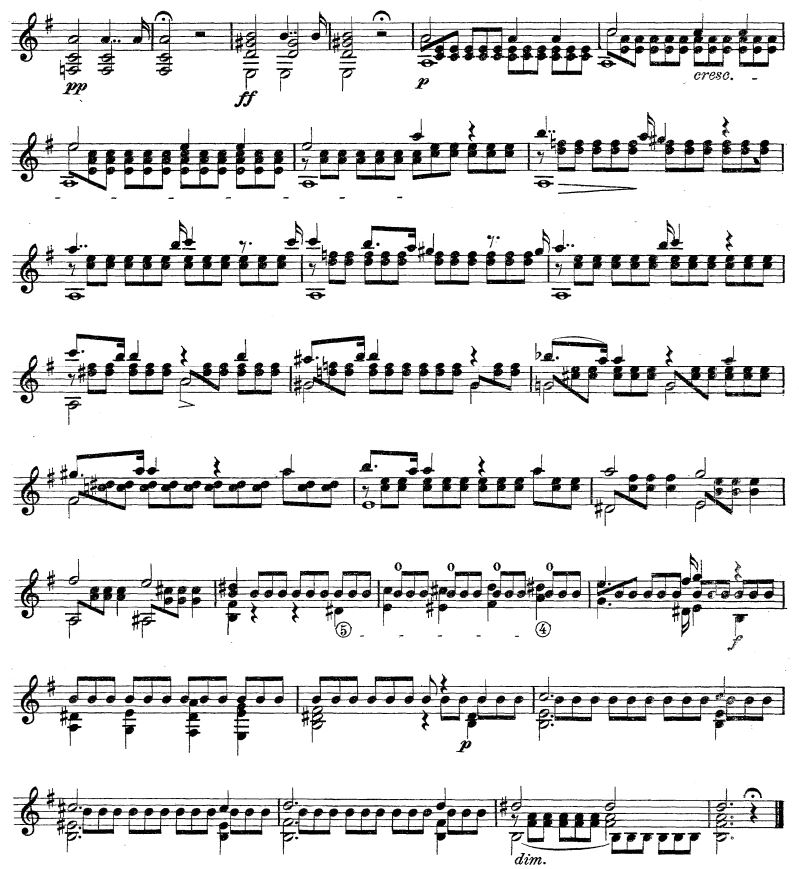

Then there is the magnificent coda (18:58 in the recording). It begins with low E pedal notes and a duet between the top and middle voices. The music then launches into a powerful forte chord progression of VI-III-IV, followed by a chromatic descent that leads to a pianissimo repeat of the march theme (with “Charlotte! Adieu!” written above the music — the work was a homage to his student, Charlotte). Next comes the final musical outburst (the VI-III-IV progression again), then a quiet cadence, and we are bid farewell with a pianissimo E minor chord that echoes the rhythm of the march motif:

So those are some of the good and interesting things about the Fantaisie. Now, onto the less good. Some of music is unconvincingly grand and drawn-out, notably here (6:43 in the recording):

All that just to go from E minor to G Major to A minor and back to E Minor again. Sor is trying to build up tension as we head towards the funeral march. So he modulates to the sub-dominant and introduces an anticipatory triplet rhythm. And that’s all he does. It doesn’t live up to the obvious ambition of this section.

Uninteresting modulation weakens the tension of the entire piece. He could have easily explored more keys: a composer who wrote a brilliant ten-minute sonata movement for guitar in the uncommon key of C minor (op. 25, 1st mvt) would have certainly been capable of more interesting harmonic development.

The funeral march, when we get there (after about nine minutes), is superior to the introduction. It is less bloated, more harmonically interesting, with a greater sense of direction.

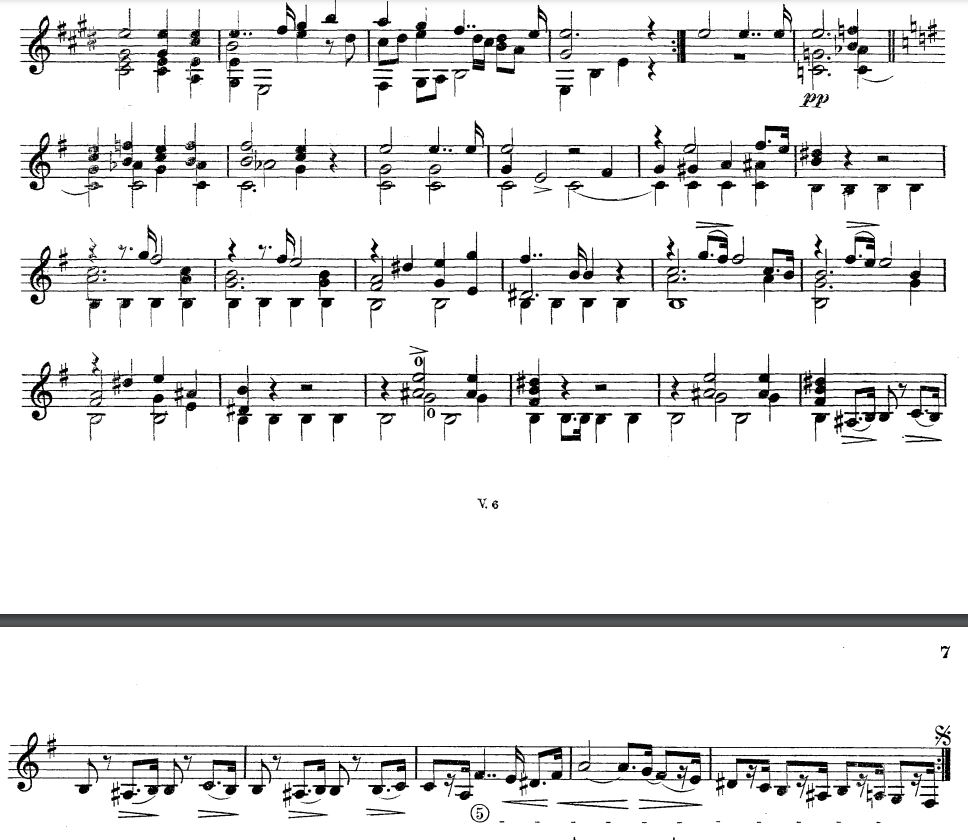

The obvious comparison is with the third movement (the funeral march) from Chopin’s Sonata No. 2. They both are structurally similar, ABA, with Sor also having a B section that is like a tender little nocturne (11:06 in the recording):

In both works the B section is, for me, the most beautiful part. It is beautiful in and of itself, but also beautiful in the way it binds together the surrounding music. However, some of the harmonic problems of the introduction return: Sor takes his time returning to the A section, with a modulation to the sub-mediant which always sounds inelegant to my ear, and then a long brood on the dominant (begins 13:09 in the recording).

Chopin, on the other hand, returns to the A section with little fuss, from Db major to Bb minor. Personally, I would be happy to cut out this entire section from Sor’s funeral march and go straight from E major back to E Minor.

Anyway, see what you think of the work. When Raphaella Smits plays it (she’s one of best interpreters around of nineneenth-century guitar music) I sometimes manage to forget (most of) my criticisms. One thing about Sor is that sometimes the virtues of his work can be more apparent in performance than on the page.

Leave a comment